Braintree Clock Repair by post / mail.

Increasingly I am being asked to do clocks from further afield. Further, frankly, than it is economical to drive. Due to what appears to be an expanding reputation regionally I have now done a few jobs by post. This has worked well but I run it a certain way to make sure it all goes well and good communication is maintained.

What to do if you want your clock repaired by post / mail.

If you want to send me your clock its really the best idea to ring me as well as email me in the first instance, so include your phone number in your email or text. Long email exchanges are not the way to go about diagnosing a mechanical fault, so a quick email about the nature of the problem with your phone number and any pictures you can provide is the best start to things.

I’ve got very good at assessing problems via a quick and gentle interrogation (!) on the basics and from thereon the conversation can quickly move to a fairly accurate estimate. Having said this I normally end up having an extended clock-centric chat with my customers on various clock related issues which I thoroughly enjoy and often learn a thing or two. Contact me as described above on email at admin@braintreeclockrepairs.co.uk or on 07462269529

How to send the clock to me

If, after speaking to me, its decided to post the clock then pack the clock properly with good materials designed to do the job. Use bubble wrap, polystyrene worms / beads, or I have found that a lot of screwed up newspaper balls does a really good job if you pack them tightly. Pack at least 4-6 inches around all the clocks sides – if this means using a bigger box that you first envisaged, then so bit it.

While it costs more to send because it will most clocks into the medium royal mail package price band, its well worth it. If the clock arrives with structural damage during transit then estimates for work will at least double. Smashed convex glass in most cases has to be sought and bought internationally for instance. Some, like Smiths deco era square convex glass (think top of soap bar shape) is almost impossible to get hold of without buying an entire orignal and probably working clock to butcher to spares. I am only pointing this out because you might be surprised that fixing the outside of a clock can be more expensive than fixing what goes on inside and how rare the fixtures and fittings on it have become. Your investment in good packaging is valuable insurance.

Send the Clock To:

Justin Holt

Braintree Clock Repairs

59 Notley Road

Braintree

Essex

CM7 1HE

How long it is likely to take to repair your clock

My turnaround varies. It s depends on several factors such as parts availability and delivery time, current workload, which is generally one to two weeks ahead. However its often more efficient to do some of the smaller jobs earlier than they arrived in date order. For a tricky clock with multiple problems – say a 1910 Ansonsia American Wall clock that “just stops sometimes” its can be a 3 or 4 week process of testing faults that can take days to manifest on test runs.

So really there is not delivery timescale promise at all really but what I will say is that I have never been chased on a job and have been complimented more than once with excellent turnaround time, so read into that what you will!. I think the fact of the mater is that people sort of know when a clock has something seriously wrong with it and are realisitic on how long its going to take to fix. Their unspoken estimate must match my own!. It would be convenient if you could post the clock to me so it arrives on a Monday or Tuesday. These are my reserved tooling workshop days and I am generally in to receive deliveries although I have a local postal depot quite close where I can pick up from relatively easily if you need to post on days off during the week or suchlike

Special considerations when you want your carriage clock repaired by post

Carriage Clocks and Clocks with Platform Escapements are long jobs and the parts are expensive. Its at the higher end of costs so expect a bill of no less that £240 for a basic service on a chiming clock.

If main spring on the clock needs replacing add £80 to the £240 service.

If the platform escapement has worn out or is broken its not worth getting them fixed – it just ends up being too expensive compared to fitting an accurate modern platform escapement that can be sourced for £100 or so. This may involve drilling new locating holes wich need to be die tapped and/or reshaping the chasis of the platform escapement with a cutter or grinder. Its a fair amount of work.

If the cogs are gone it become prohibitively expensive to have them made. Basicly you need a laser cutting clock part making machine. These cost about £250k for a good one of those that can do watch parts as well….. so that particular Braintree Clock Repairs service is not available directly for the meantime (ehem!). Essentially, I have to contract that element out but it really doesn’t make it much easier as you have to know what to specify in terms of dimensions – information you cannot retrieve from a worn part. Its much easier with Grandfather clock components for instance, where you can measure where things should be and specify to within .1mm without worrying. With carriage clocks the higher wheels and the platform escapement itself are really closer to a pocket watch – small fiddly un-measureable tolerances. I don’t do watches for this reason – you cant really craft anything yourself.

All that said, costs are not prohibitive in most cases unless the clock is a particularly fine one with several problems. A small Matthew Norman (not a chimer) is around £100 – £150 to service. As a mainstream modern clock its also much easier to find after market parts that will fit so even if the platform escapement needs replacing this can be done for between £150-250 depending on the model and including a service clean,

Insure your clock as part of the shipping cost / option – its standard service on Royal Mail. I will insure it for the same value on return. I far prefer Royal Mail to any other carrier – they really are much easier for me (thanks).

Well going global was easy. Done!.

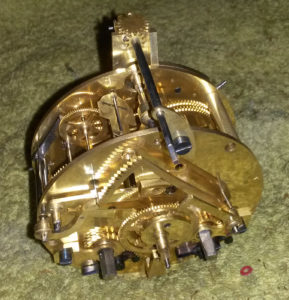

This is a clock thats just been serviced and repaired on my testing jigg. Im narrowing down the accuracy ready for delivery in a couple of days.

This is a clock thats just been serviced and repaired on my testing jigg. Im narrowing down the accuracy ready for delivery in a couple of days.

Recent Comments