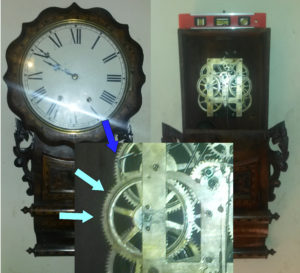

This is just a quick article to show you roughly whats involved and how you go about things if you want to replace a broken clock mainspring. Its quite a challenge on any clock so Ive selected a particularly simple movement to show whats done. This article is for somebody who already knows how to take apart and put back together a simple movement – a beginner with a bit of talent. Mainspring breaks and replacements are a common problem so I thought I would do an overview article on roughly whats invloved and how to go about it.

How do you tell if your clock mainspring is broken?

You can tell if your mainspring is broken because the clock key will offer little or no real resistance when you try and wind the clock. If the spring has broken in the middle this may be a little different; in this case the clock will wind for maybe two or three turns but then you will hear the spring move and the resisitance on the key will go down again. In either case you will need to have it replaced.

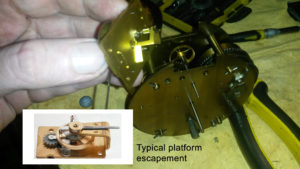

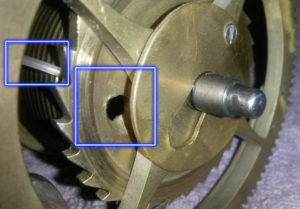

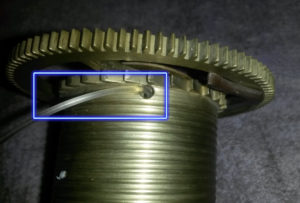

As you can see from this picture the main spring here has broken and needs replacing. Note the that spring has broken about five or ten centimeters from the barrel spiggot and there is still about 120 cm of spring braced tightly to the edge of the barrel.

Removing a broken clock mainspring

To remove this force a sharp wide object (I used a sharpened bradel) in between the wound spring layers. You want to lift the spring so you can get some long nosed pliers in the gap. Once you have done this grip the spring with the pliers and STOP.

If you pull the spring out now it will unwind like a whip cracking and you could easily be injured because your likely to be holding the barrel with your other hand and this is the area the spring will be at its most dangerous.

To avoid this wrap it in a towel so you can only the handle of the pliers sticking out of what should look like a big chelsea bun or turban (sorry turban guys – no offence meant its just that if it looks like a turban your doing it right!).

Now you can pull the spring out with the pliers and the towel will dampen the expansion of the spring. When you see it go “splong” you will realise the turban towell is a very good idea indeed. If its a thick spring e.g. the spring thickness looks over half a mm then take particular care and double towel it – the spring is strong and will unwind like a flying blade. I have injured myself hurrying things and not bothering with the towel – unwise, and the sort of thing you learn early and quickly in clock tear down and rebuild.

Once the spring is out then you need a vernier gauge or micrometer to measure the spring in order to source an identical replacement. If the movement is worn then you might like to go for a stronger thicker spring but not by more than .1 or .2mm. This can put a bit of life into the chiming spring if the coggs are worn in the clock and its all a bit loose.

How to measure a broken clock spring and how to search for one online.

Springs are measured in three dimensions for specifications purposes. Firstly the thickness which ranges from .3mm to about .7mm for a typical mantle clock. Your going to have to bend a portion of the spring flat in order to get an accurate reading. An accurate reading to .1mm is essentail for success and if your not sure round the number up as opposed to down.

The second measurement is the height of the spring – typically between 15 and 40mm. 40mm is likely to be quite a thick spring as well – simply dont attempt these larger ones – genuinely dangerous. As a first timer really dont attempt anything over about 20mm and thats pushing it. If your going to have a go at this the best idea is to buy a cheap old broken clock and dismember it on the assumption its not going back together again – a training clock in essence.

Lastly you might think that the third dimension would be the length, but it is not, it is the barrel width, or more accurately the internal barrel width. A vernier guage should be used to measure this last dimension. So, the spring I used in this clock is described as a .3 x 20 x 30; a relatively weak and safe spring to work with.

Preparing your replacement clock spring

Your spring will arrive from your supplier looking like this.

Before going any further lubricate the spring with clock oil. Soak it and then dry off the excess. If you have been lucky enough to source a spring that is 3 to 5mm less in diameter than you need for the barrel, then you can just put in in there. The problem is that if you go for this option the spring overall may not give you the 8 days of wind you ideally want or worse, it might not provide enough power to drive a worn movement. The movment is likely to be worn because a spring will last a good 30 years in my experience.

Installing the new clock mainspring and about spring winders…. do you need one (yes = safe, no = highly risky)

To insert the spring into the barell use the wire wrapped round the spring as a brace agains the top of the barrel wall and then push the spring in while the wire remains braced above / on the barrel edge to about 3mm. I have found that tapping the spring in this way slowly until its almost released for the wire is the best way and then finally give it a fairly punchy hit with a flat object – a flat piece of wood is ideal if you place the wood on the top and then hit the wood with a mallet. if your lucky the spring will go in completely flat but this rarely happens. The edge of the spring is more than likely sticking up at the edges. You need to correct this or the barrel cap wont fit back on. To do this use a screwdrive or flat punch to kock the spring edge in flat. Do this bit by bit around the entire edge until you can see tha the barrel cap has enough room at the edges to to back on flat and in line with the barrel circumference edge which will normall have inset seating in the barrel you can see.

You will also need to line up the hole on the outside of the barrel with the peg inside the barrel wall that is there to hold it when wound. If you find you miss it dont worry to much as this will either correct itself when you wind the spring or it will stay in place which is perfectly ok, if not perfectly correct. It will also lead to some premature ageing on the spring but nothing you need to forcast for e.g. 20 years. The peg inside the barrel is the reason a 30mm diameter spring will not slide into a 30mm barrel fully.

This is why you need a spring winder. Strictly speaking the spring should be unwound fully (released from its wire holdings) and then rewound and rebound with wire in the same fashion as before. In short you need a spring winder to do the job properly. These can be bought from online and you need to look at a few to decide which one you really need based on the sizes of springs your intend to work on. I tend to work on a lot of mantle clocks so thats what I bought mine based on.

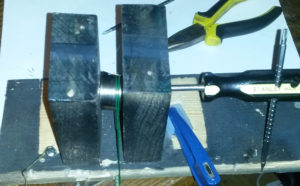

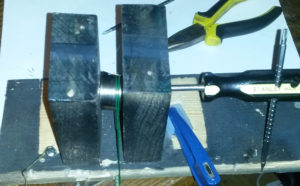

For an experiment I built my own spring winder. I was not too ambitious with the design and opted for one that would handle only one spring type. It really wasnt that difficult although I wouldnt dare use it on anything over a relatively safe and weak guage spring as there were several “malfunctions” during its prototype phase and during use.

My honest advice on this “do it yourself spring winder” is dont attempt it because its dangerous as well as painfull when a spring unwinds on your fingers. I am very used to working with springs and know what Im dealing with in terms of forces and tolerances – you probably dont yet so proceed carefully with any of your own inventions if you find yourself compelled to tinker. I have to say I had great fun building this jigg and it was not as easy as I expected. I wouldnt do it again in light of the risks and various injuries I sustained.

In essence you can see whats going on from the picture. The only thing you cant see is that the shaft of the screwdriver has a spiggot on it.

I embedded this spiggot with an HSS drill bit and using good carbon steel for the spiggot itself but made sure the screwdriver was soft \ cheap and therefore easier to drill. The green wire holding the springkeeps it taught and fixed at the outer edge, while the scredriver is turned to compress the spring. As you turn the handle the spring compresses and reduced diameter. Every few turns you measure diameter with a vernier guage. This is the point I sustained most finger bruises and cuts because I had to get close to the spring to measure it and measuring invloved touching it – a bad idea as I found out.

Its easier to drill lower quality steel when you make things generally speaking and you really need a couple of hundred pounds to buy a standing industrial quality drill for any kind of engineering clock repair. I had one already of course but if you want to cost this all out well… ehem is all I can really add. The point of building this was simply to see if it could be done and connect a little bit with the ethos of the clock makers of old. Us clockists really respect the early makers and methods simply because you realise people did all this precision mathematically driven work with hand tools and jiggs. It really is astonishing when you look at some of the pre 1800 clocks and take on board the level of engineering and mathematical knowledge that is essentail in the production of a hand made clock. This is my little contribution to the craft…appalling effort, but an effort none the less. And it worked.

Alligning the barrel spiggot on a new clock mainspring.

Once youve got the spring in the barrel the next important part is making sure the spiggots hook catches the spring when you turn it clockwise. You will see how this works when you do it. Its likely you will need to bend the spring towards the centre of the barell so that its pressed against it when its at rest and vertical. When you bend the spring with long nosed pliers DO NOT bend the part of the spring where the inner hold is located. The spring will overbend in this area and its also possible to bend it unevenly and differently on each side of the hole. This will lead to the spring edge being on a tilt where it connects to the spigot and can mean the hook will not be able to catch the hole as its rotated. To test if your spring connects with the spiggot correctly you need to fit the barel cap and then turn it quite aggressively. It needs to hold so there is no point of being gentle with the rotation. If it slips you will feel it, so you then remove the barell cap and re-adjust again (and again and again) until its all catching perfectly and you are absolutely sure its secure.

The reason I emphasise this testing proceedure is that if you put the whole movement together (which can take literally days on a complicated job), and it doesnt work…you have to do the whole thing all over again in terms of dissassembly / assembly.

I hope this article removes some of the trepidation for the first time spring replacement jedi trainee and I am more that happy to provide Yoda like adivice via email if you have a project you need some basic assumtions confirmed or general questions answered.

If you want me to do it for you just give me an email or ring and I can quote you on the spot if im in the workshop.

Above all – have fun with it. Its great to undertake a job like this and complete it; you really feel like youve taken a genuine step forward in your clockery expertise. I still get a buzz out of fitting a spring – your working with high tension components and you need to be careful, organised and check list based in your approach because mistakes can cost you the spring and whatever it costs for an ambulance these days….read on.

Safety Stuff that is actually worth reading and not here because I want to bore you do death.

Seriously on that point – safety. Some things you really do need during this from start to finish, if you dont have them then buy some as the very first job on the project list. Safety kit hampers movement and the speed you can work at but its essentail unless you want to lose an eye or finger. It also allows you to work more confidently as the strength of clock mainsprings generally is greater than you would expect without any experience.

- Wear good tough gloves for all operations where the spring is under pressure. You neet gloves with good all round protection, knuckls and the back of your hand are the bits that take the punishment so dont bother with gardening gloves!. Thick leather are my recommendation. The rule is that they only come off when the spring is in the barell and your in the safe zone.

- Dont attempt a home made experimental winder like mine if you are using anything over .3mm strength as even those pack a punch when they unwind when you make a mistake.

- You would have to be mad not to wear eye protection on this job. Its ABOSOLUTELY essentail. Your often looking at the spring from the angle that puts you at maximum risk – the direction it will instantly unfurl like a flying blade. If you dont wear eye protection that blade will take your eye out.

- Work with your head at least a couple of feet (60cm) away from the wound spring at all times. This is a job you do at arms length.

Dont do this job when you are distracted or at risk of distraction. Distractions interupt important processess and if you return from and interuption maybe you absent mindedly took off your safetey glasses off to put your reading ones on…. an easy mistake to make and potentailly very dangerous.

Be safe and enjoy yourselves – always happy to hear from you.

This post is mainly about dating a grandfather clock and Elvis.

This post is mainly about dating a grandfather clock and Elvis.

I estimate that this home made obelisk is about 25ft high. It was constructed from concrete reinforced with steel bar. Thats what I call commitment. The absolutely best thing about clock people is that they appreciate the better things in life. I meet tons and tons of the nicest people you can imagine and all have a story to tell. Theres something about mechanical clocks that attracts the more interesting people and they are all a pleasure to meet.

I estimate that this home made obelisk is about 25ft high. It was constructed from concrete reinforced with steel bar. Thats what I call commitment. The absolutely best thing about clock people is that they appreciate the better things in life. I meet tons and tons of the nicest people you can imagine and all have a story to tell. Theres something about mechanical clocks that attracts the more interesting people and they are all a pleasure to meet.

Recent Comments